This Post is unusually image-heavy and may not display in full in some email clients; you may prefer to open it in a browser or in the Substack app.

Last week it was Reliable Narrators (with a question mark); this week I’m considering the reliability (or otherwise) of my own memories.

A small instance to start: late last year, I picked up Zadie Smith’s On Beauty in an Oxfam bookshop. No surprise that it’s a great read; the surprise was that my memory of when and where I first read it was all wrong. I’d convinced myself that I’d first read it when I was working part-time as a porter in Lancaster University Library. But that’s not possible: On Beauty wasn’t published until 2005, and I left that job to become a full-time outdoor writer and photographer in 1994—when Zadie Smith was just nineteen. Prodigiously talented as she is, it would have been a mammoth ask to write and publish such an ambitious novel at that age1.

It’s not that I made a mistake; that’s all too familiar a feeling (says the guy who left his keys in the front door [on the outside, just to be clear] for four hours today). It’s that I had such a clear image of myself reading the book in the Porters’ Lodge during quiet periods on the evening shift.

And if I can mislead myself, on something like this, to such a degree—it’s eleven years, after all—how far can I trust some of my other memories? Like the stories I’ve previously shared on Substack, as in this Post on how I first encountered some of my favourite books and authors. Well, I still have no doubt that my first Pratchett was Wyrd Sisters, or that I found it among lost property in the same Library. I’m equally certain that I first picked up Pride and Prejudice in Islamabad. I don’t think that’s a detail I’d invent (well, perhaps I would, in fiction).

However, I see, revisiting the post, that I’ve admitted to being a little hazy as to whether I borrowed my friend Robin’s copy of The Lord of the Rings for my first read, or whether I bought it straight off, or maybe even found it in the College Library. If I’m hazy about a detail like that, how far do I trust a memory from ten years earlier, my tale of how I first read Swallows and Amazons?

I’m pretty sure the key point is true: that my Mum handed me a copy to keep me amused at a wedding reception2; but was I nine? Might I have been younger? And was it in Warrington? This is quite likely, because her family were from that part of the world, but for the same reason it could be a detail I’ve filled in later. I do know that I quoted the tale in the Introduction to my first book on Ransome, and pointed it out when I gave her a copy, and she never challenged any part of it.

And then there’s a whole swathe of mostly adolescent memories that were called into question a few years ago. Just to underline the whole point, my first thought was that the book which I’m mostly referencing here was one of the last (most recent) of my non-fiction career. But when I went back to my records to check it turns out that it was published in 2013 and is only no 46 on the chronological list of my 61 traditionally published non-fiction titles3.

The book in question is Lancaster Through Time, published by Amberley Publishing4.

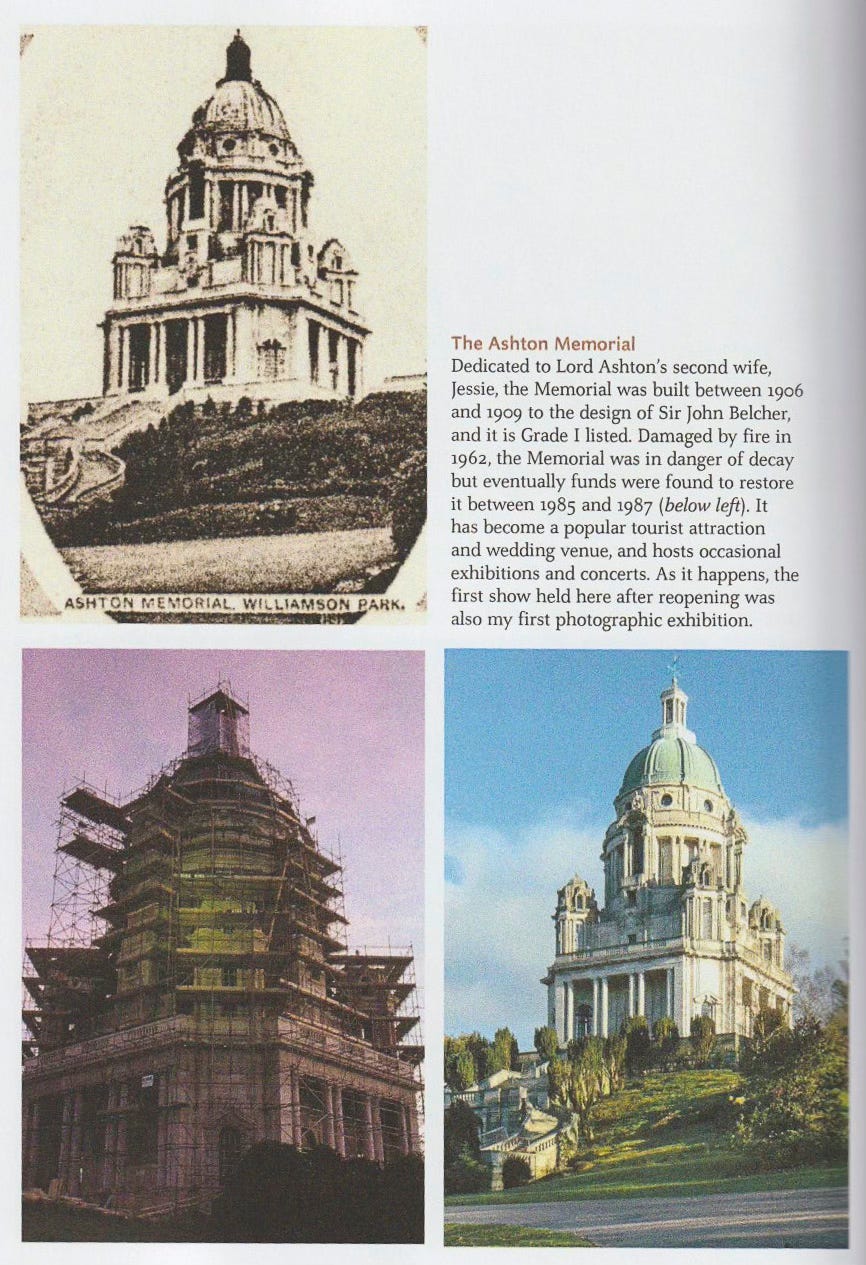

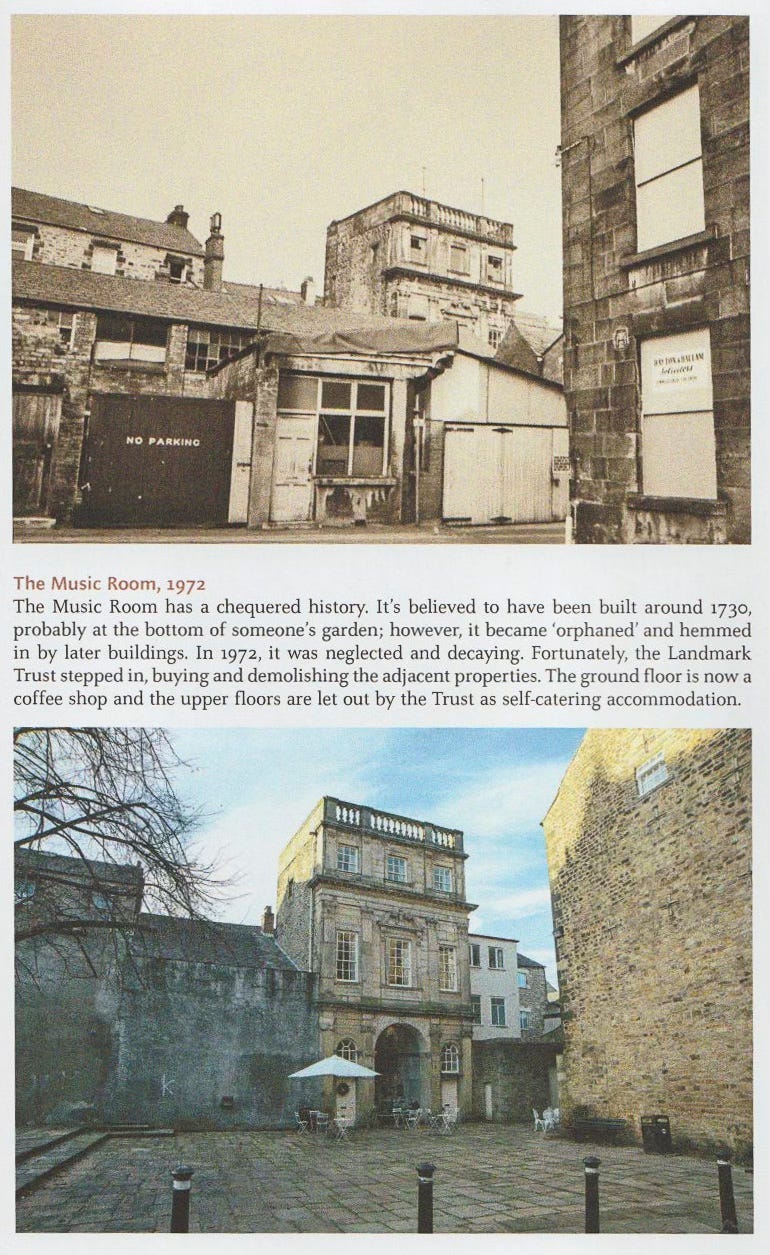

As soon as you see the title you almost certainly know what sort of book it is. You collect a bunch of old photos (with due diligence to avoid infringing anyone’s copyright), and couple them with contemporary images of the same locations—as nearly as locations can be determined, and with due regard to safety. A photographer in 1880 might have been able to set up a tripod in the middle of one of Lancaster’s main streets5. Anyway, you get the picture, or 150 pictures.

It seems, from my own perusal of a few such titles, that the historic images tend to skew towards 19th and very early 20th century sources. Which of course is fascinating; but I was keen to broaden the scope a bit, for two main reasons. One was that I felt sure a lot of people would be interested in images from their own lifetime, or that of their parents’ generation. The second was simply one of availability.

There are some great archives of historic photography and film, notably the Frith collection and, in my part of the world, the Mitchell and Kenyon archive. But these are tied up with copyright and licensing issues. I have no problem with the principle. Collecting, preserving, and archiving material like this is an important and expensive business, and needs to be funded somehow. But it does mean I couldn’t afford to use their images. And as I searched for alternative sources, I came across a treasure trove of material hosted online by a guy named Graham Hibbert, specific to Lancaster and mostly dating to the 1960s and 70s.

Quite apart from its value to the book, this collection was fascinating to me personally. My family moved to Lancaster in 1968, just in time for me to start at grammar school6. Apart from four years when half the year was spent away at University, I lived there until 2006, and still live only ten miles away. It’s the place I call my home town.

I fondly thought the images would stir up loads of dormant memories. What I hadn’t anticipated was how far, and how often, image and memory would clash. And, above all, how run-down and grimy and, above all, drab, it mostly looked.

Hang on… weren’t the 70s, and especially the first half of the decade, the glam rock years?

David Bowie, Space Oddity, 1969; Starman, Jean Genie, 1972; Life on Mars, 1973

T. Rex, Ride a White Swan, 1970; Get it On, Jeepster, 1971; Metal Guru, Children of the Revolution, 1972

Roxy Music, Virginia Plain, 1972.

Admittedly for me these were more the years of Emerson Lake and Palmer (Trilogy, 1972, was my first of their albums), and Yes (I still occasionally play Close to the Edge, released the same year). But if you think about bands like these, their costumes and stage acts were pretty 'glam' too. (Not that we 'progressive rock’ snobs were over-keen to admit any affinities back then.)

I wonder if this is part of the reason that an aura of glamour still hangs over this decade for many? Well, simple arithmetic means that if you can remember the 70s at all, you aren’t exactly young any more. It’s an uncomfortable thought that every one of the singles and albums mentioned is now over 50 years old. Marc Bolan died in 1977, David Bowie in 2016, the same year as both Keith Emerson and Greg Lake; it begins to seem pretty impressive that four of the five members of Yes’s Close to the Edge line up are still alive.

But this isn’t meant to be a post about glam- vs prog-rock. It’s about memory, and now it’s about Lancaster. And it’s about the 1970s, a decade which may have a seductive aura for some but actually saw the The Three-Day Week (1974, when I was in Sixth Form) and, near the end of the decade, the so-called Winter of Discontent (which spawned one of the most damaging newspaper headlines any Prime Minister has ever faced, "Crisis? What Crisis?"). Per capita GDP did grow through most of the decade, but even at the end was only about half, in real terms, of its present value.

If you’re enjoying this piece and you’d like to show appreciation without becoming a paid subscriber, you could always…

And Lancaster… well, Lancaster’s glory days as a significant port (with inevitable links to slavery) were long past. In the 19th century it was primarily a manufacturing town, producing cotton and linoleum. Like many Northern towns it had suffered heavily from the decline of these traditional industries. Its undoubted revival since owes a great deal to the advent of Lancaster University, founded in 1964, but still relatively small in the early 70s7, and something to a growth in tourism. (I’d play a small part in this myself, but not until the 1990s). If Lancaster in the mid-70s looks run-down in the photos, that’s at least partly because it was. And bear in mind that I looked at dozens, if not hundreds, more 1970s images during the preparation of the book.

But how much of this did I see at the time? Apparently, not as much as I thought—or else those memories have been overlain by later ones. I suspect the 1990s carry particular heft in this respect, as that’s when I spent a lot of time prowling the city looking for choice bits to photograph for Lancaster Tourism, for a City Calendar, and for my own postcards, greetings cards, and Christmas cards, among other things. I even went back to my old school to do photography for a prospectus and other publicity. Inevitably in all these endeavours I was looking for the good bits—and I’m sure plenty of places had received at least a lick of paint.

There is another factor, in that the photos from the 60s and 70s, whether prints or transparencies, were often notably faded, with colour shifts and loss of saturation. I chose not to try and enhance these too much, because without an accurate reference for the original colours it’s all too easy to get it wrong. Still, I know enough about photography not to be too far misled by the deterioration of the images, and there’s plenty of substance to focus on.

Conclusions? Nothing very profound, except to remind myself not to place too much trust in my own memories. I thought I’d wind up with a few of the photo pairings which seem to illustrate what I’m talking about.

Yes, I can cite prodigies too, from Mozart to Kate Bush (wrote Wuthering Heights at 18, had a massive No. 1 hit at 19), but let’s steer clear of that particular rabbit-hole.

I’ve carried a copy to every wedding I’ve been to since. And if you believe that…

To which you can add a couple of self-published non-fiction ebooks and a self-published picture book (via Blurb) as well as five self-published novels to date.

Still in print, and still earning me a trickle of royalties.

Tripod or not, they certainly did get the shot from the middle of the road. I think I took mine almost on the run as the lights were changing….

For US readers, 'grammar school' in the UK is one strand of secondary education, which most of us start at 11 and continue to 16 at earliest.

Not so small now; in the 21st century it’s been consistently ranked top-15 on the main league tables.