Exploring the Borderlands

Golden Witchbreed: An Appreciation

I recently read a fine post by Clifford Stumme on the difference between SF and Fantasy. In the discussion we were speculating about writers who’ve bridged the divide (and if indeed there is one) and written both. Clifford’s post itself was stuffed with quotes from Ursula K Le Guin, which is always a plus for me, but three more names immediately sprang to mind: Terry Pratchett, C J Cherryh, and M John Harrison. There are dozens more.

And then I went off on a tangent: what about writers who’ve introduced fantasy tropes into by-definition SF1? None more obvious than Anne McCaffrey, with Dragonflight (1968) and its 20+ sequels exuberantly melding dragons, and the quasi-mediaeval setting so familiar in fantasy from Middle-earth to Discworld, with an unmistakably SF backstory. (As I mentioned in an earlier post, there’s a similar blend in Ursula K. Le Guin’s first novel, Rocannon’s World.)

For all my affection for Dragonflight, my tangent didn’t stop there. Instead it took me quickly on to another author, and one book in particular, which I loved on first reading and have relished all over again on probably five or six re-readings (with a rapid read just now in search of a few useful quotes). It’s clearly a science fiction novel, but there’s so much about it that feels like fantasy. It lives in the borderlands.

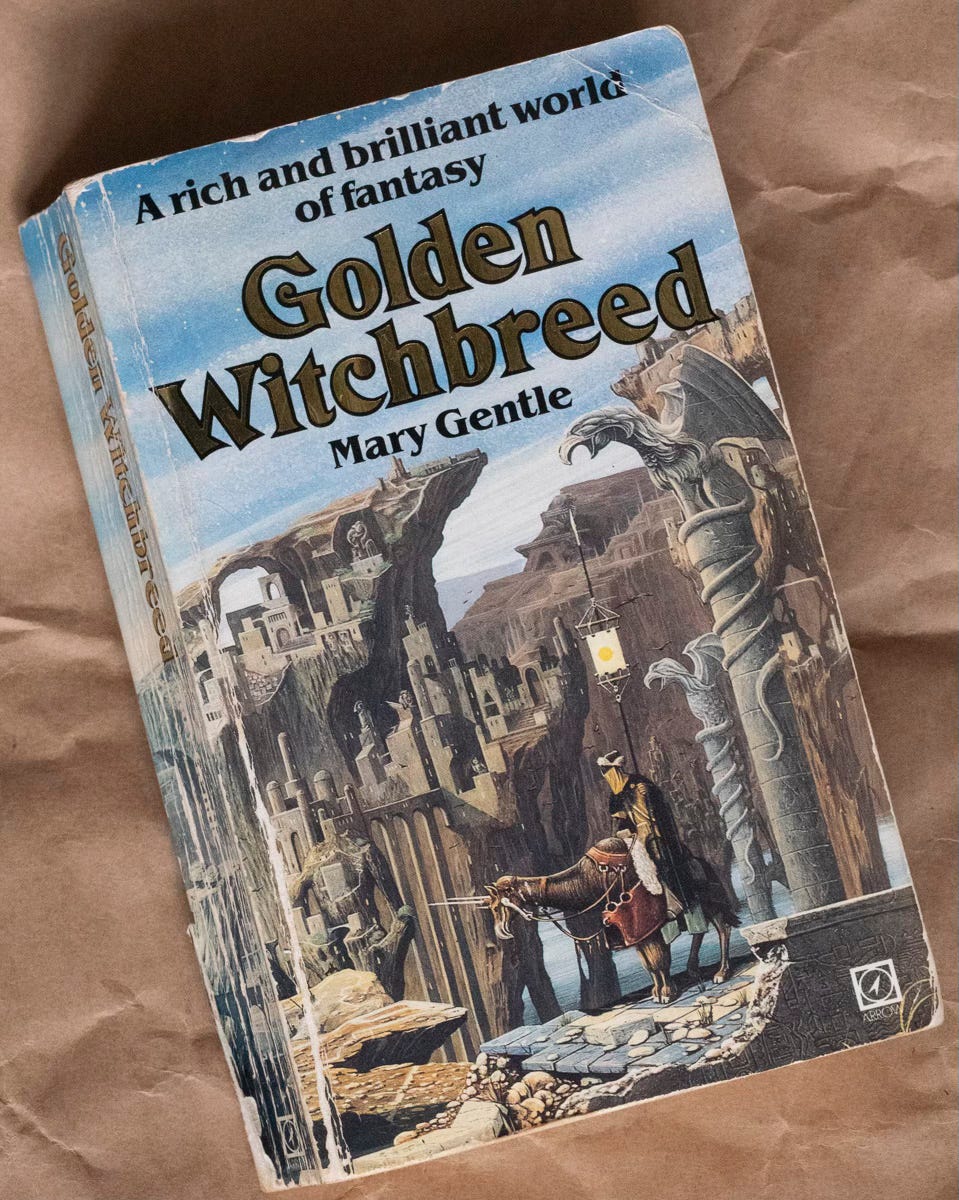

The book is Golden Witchbreed by Mary Gentle, first published in 1983. My copy is from the first paperback edition, of 1984, and I suspect I bought it soon after it came out.

It’s the story of Lynne de Lisle Christie, a young envoy of the Dominion of Earth, beginning with her arrival on the remote world of Orthe. We’re aware from the start that it’s SF, with mention of starships and shuttles on the very first page, but all this rapidly recedes into the far background as Christie proceeds to the city of Tathcaer by sailing-ship. When she embarks on her journey around the rural hinterland, the only trace of advanced technology she carries with her is a small medical kit and a 'sonic stunner', but most fighting is done with blades2.

Christie’s travels bring revelations about the true nature of the nearly-human Ortheans and their society. It slowly becomes clear that Orthe is not a pre-technological world but a post-technological one; a world, in fact, which deliberately shuns higher technology, though some traces survive.

Advanced technology is closely linked with the reviled name of the Golden Witchbreed, a race that once ruled Orthe, treating the general populace as slaves (‘beastmen’). There are factions which believe, or at least suspect, that Christie and her kind are not off-worlders but agents of some remnant of the Witchbreed. The story unfolds amid constant intrigue, alliances shifting like playing-pieces in the game ochmir3, and where assassination is by no means unheard of as a political move. There are betrayals, too, before the end.

Comparisons with Ursula K Le Guin are obvious, and specifically with The Left Hand of Darkness, published fourteen years before Golden Witchbreed. For instance:

—Like Christie, Left Hand’s MC, Genly Ai, is an envoy (both books used this specific term) from an advanced civilisation to a lower-tech world;

—Like Christie, Genly initially struggles to adapt to the culture of the world, an important element of which is the understanding of gender (more on this below);

—In both books, the MC begins their exploration in a nation which is hierarchic, monarchical, and deeply traditional;

—Christie is an empath; Genly is adept in the technique of mindspeech;

—Both narratives hinge around an arduous journey in winter conditions;

—Both MCs develop very close relationships with one or more of the natives.

None of this should be taken to suggest that Golden Witchbreed is derivative, except in the way that all good books (and no doubt plenty of bad ones too) build on sound foundations. The theme of first contact between high-tech and less 'advanced' civilisations is an enduring one in SF. Consider how many episodes of the various incarnations of Star Trek hinge on Starfleet’s Prime Directive or principle of noninterference. (If it’s more often honoured in the breach than in the observance, well, that’s James T. Kirk for you.) Or note how Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest prefigures significant aspects of Avatar.

I began to accept the fact that here, on this world, I was the alien.

(This, and the following pull-quotes, are all from Golden Witchbreed.)

Examinations of gender/sex, whether through fundamental biological differences or merely societal roles, were not exactly new either, but The Left Hand of Darkness was hugely significant in placing them centre-stage. But this must say something about the zeitgeist of the times. Germaine Greer ’s The Female Eunuch appeared the year after The Left Hand… was published, but this was twenty years after de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex and six years after Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Another seminal work of feminist SF, Joanna Russ’s The Female Man, appeared in 1975 but was written in 1970.

Still, one can see specific connections between The Left Hand of Darkness and Golden Witchbreed in their treatment of gender. The people of Gethen are neuter except in short monthly periods of kemmer, when genitalia rapidly appear and sex becomes possible. An individual may manifest as male at one time, female another, and it is quite normal to have been both mother and father at different times. Genly Ai, permanently male, is viewed by some as a 'pervert’. Ortheans are also neutral until late adolescence, when a short but intense transition presages emergence as male or female. Gethenians spend most of their lives as neuter; Ortheans are socialised and develop their character before any assignment of gender.

It’s always hard to tell any Orthean’s gender, but Maric had come out of ashiren a young woman.

In both books, gender roles and expectations are more flexible than in most traditional societies. In The Left Hand of Darkness, lines like ‘my landlady, a voluble man' are perfectly comprehensible. In Golden Witchbreed, the commander of the Southland’s army (and the primary Orthean character), Ruric, is female4.

Whatever the points of similarity, Golden Witchbreed stands solidly on its own merits. The world-building is rich and vivid, characters are fully three-dimensional, and Gentle’s prose is lucid and evocative. Yes, you could say all this about Le Guin, and about many other authors, but Golden Witchbreed has a voice and a sensibility all of its own.

For me there are resonances which leave me wondering why I hadn’t specifically considered Golden Witchbreed as a personal inspiration before now. Recall where this post began, with the intersection between SF and fantasy. I may not have had a plan when I began writing Three Kinds of North, but I did know that I wanted the story and its setting to feel more like fantasy than hard SF. The Dawnsingers remain something of an enigma even after Jerya is unexpectedly precipitated into their midst. Yes, it’s eventually clear that they have no magical powers, but we’re well past halfway before this revelation.

The setting is again low-tech; over succeeding books it becomes clearer that society, in both the Sung Lands and the Five Principalities, is close to the emergence of an industrial revolution, but we’re not there yet. Transport principally relies on horses or sailing ships. It also emerges that the world is in a slow recovery from some distant apocalypse, which is known more through rumour than certain fact; this is very close to the premise of Golden Witchbreed.

After I’d seen steam and clockwork mechanisms, weaving machines, gunpowder and primitive electric motors, I decided that the Southland could have an Industrial Revolution any time it liked. And after I’d seen the devices dismantled and ignored by their inventors, I understood why they would not.

However (I hope), the connections aren’t solely in programmatic elements like these. I hope, with at least moderate confidence, that books like Golden Witchbreed have influenced me in other, subtler, ways. The depth of worldbuilding (conveyed without protracted infodumps), the richness of characters, the quality of storytelling, are all worthy qualities to aspire to. But perhaps the most important way in which Golden Witchbreed, like Rocannon’s World and The Left Hand of Darkness, has left its mark on me is in the realisation that science fiction does not have to rely on warp drives or androids, let alone dog-fights (at World War Two velocities) above the Death Star. Science fiction, as has often been said, rests on one basic question: what if?

And I’m left wondering: what if I’d never stumbled across any of these books, specifically Golden Witchbreed? Would the world of The Shattered Moon be different? Somehow, I’m sure it would… if it existed at all.

I’d still have been a writer; of that I’m certain. But I don’t believe I would have been quite the same writer.

Afternote:

There is a sequel to Golden Witchbreed, titled Ancient Light, published in 1987. It’s good, of course, but I’ve never been able to love it as I do Golden Witchbreed. There’s a bleakness about it that’s missing from its predecessor. There’s plenty in Golden Witchbreed that carries the potential for this downbeat conclusion, but my first reaction on reading Ancient Light was shock and dismay. It’s not that I demand every book have a happy ending, but I reject the notion that, in literature, darker equals better, or more grown-up. There’s room for both. Unrelieved cynicism is not 'grown up. It’s not even healthy, as a recent New Scientist feature makes clear. And this is giving me ideas for a future post…

When I was a youth devouring Asimov, Clarke and Heinlein, it was 'SF' and only non-initiates called it 'sci-fi'. I sometimes wonder if I’m the last holdout still clinging to 'SF'.

Mary Gentle herself is an accomplished sword-fighter.

A game, and a metaphor.

OK, before anyone mentions Boudicca or Joan of Arc, traditional societies do sometimes have female military leaders.