I've mentioned before that when I started (a long time ago!), Books One and Two were just one hefty volume, originally called The Shattered Moon. I've never regretted the decision to split them into two, as each has its own shape, or to turn The Shattered Moon into the series title. Of course there is a continuity, and The Sundering Wall does pick up more or less immediately from the end of Three Kinds of North (next morning, in fact).

In any case, no one who's read Three Kinds of North will have any difficulty working out what comes next: Jerya, Rodal, and Railu strike out into the mountains. Mountains, you'll recall, which to the best of anyone’s knowledge are unmapped and untrodden in this age of the world.

How much more can I say without too many spoilers? Well, the first thing to say is that anyone who really wants to know the outcome can find some pretty whopping spoilers on my website, in the form of the blurbs for Books Three and Four (all available right now, folks).

Still, out of kindness to those who haven’t yet read beyond Book One, I’m being reticent here. However, it’s self-evident that there are only a few possible plot-lines for the next phase; at the most basic level, they either cross the mountains, or they don't. And you can’t even look at the blurb for The Sundering Wall without gathering something about what happens after they're done with that endeavour.

So… yes, they do eventually succeed, though it's touch and go at times. The real meat of the story is what they find there and how each of them deals with it, and perhaps how they’re changed by it. But I don’t need to go into all that here, because what I want to delve into is the experiences that I've drawn on in writing their mountain journey.

Above is a 'moodboard' of photos which resonate for me with various scenes from the books. No doubt you’ve spotted several which might relate to Jerya, Rodal, and Railu's mountain journey, so let’s look at these individually.

The French side of the Brèche de Roland, in the Pyrenees. This is a close match for the second pass crossed by Jerya, Rodal, and Railu in The Sundering Wall, and one instance where I absolutely had a specific location in mind.

Our stint in the region began by walking from Gavarnie, via its spectacular Cirque, to the Refuge de la Brèche (aka Refuge des Sarradets) for the night. We crossed the Brèche the next day, but not in clear weather like this, so we had some tricky route-finding to reach the refuge on the Spanish side. It was early season so the climb to the Brèche was on snow rather than scree, which was all to the good, but the snow was less helpful later as it obscured some paths and route markings. Still, we had a map, and a compass, and always a good general idea of where we were. And we knew there was another cosy rifugio waiting for us, so we were better off in many ways than Jerya, Rodal, and Railu .

Above is the head of the Ordesa Canyon, which we descended the day after crossing the Brèche; this relates to a later scene, though not so precisely. The general topography is similar, but the detail of the descent (which Jerya revisits as a climb in Vows and Watersheds) owes as much to scrambling in the Lake District, where routes close to waterfalls are quite a speciality, as seen below.

Just to finish the Pyrenees story, we descended the Canyon to the village of Torla where we spent two nights, exploring Ordesa a bit more on the intervening day, before crossing back into France by an easier route. We then returned to the Refuge de la Brèche, from where we repeated the climb to the Brèche in clear weather—and it was worth it for the views.

The other two images from the moodboard are more about feeling than any specific bit of their journey.

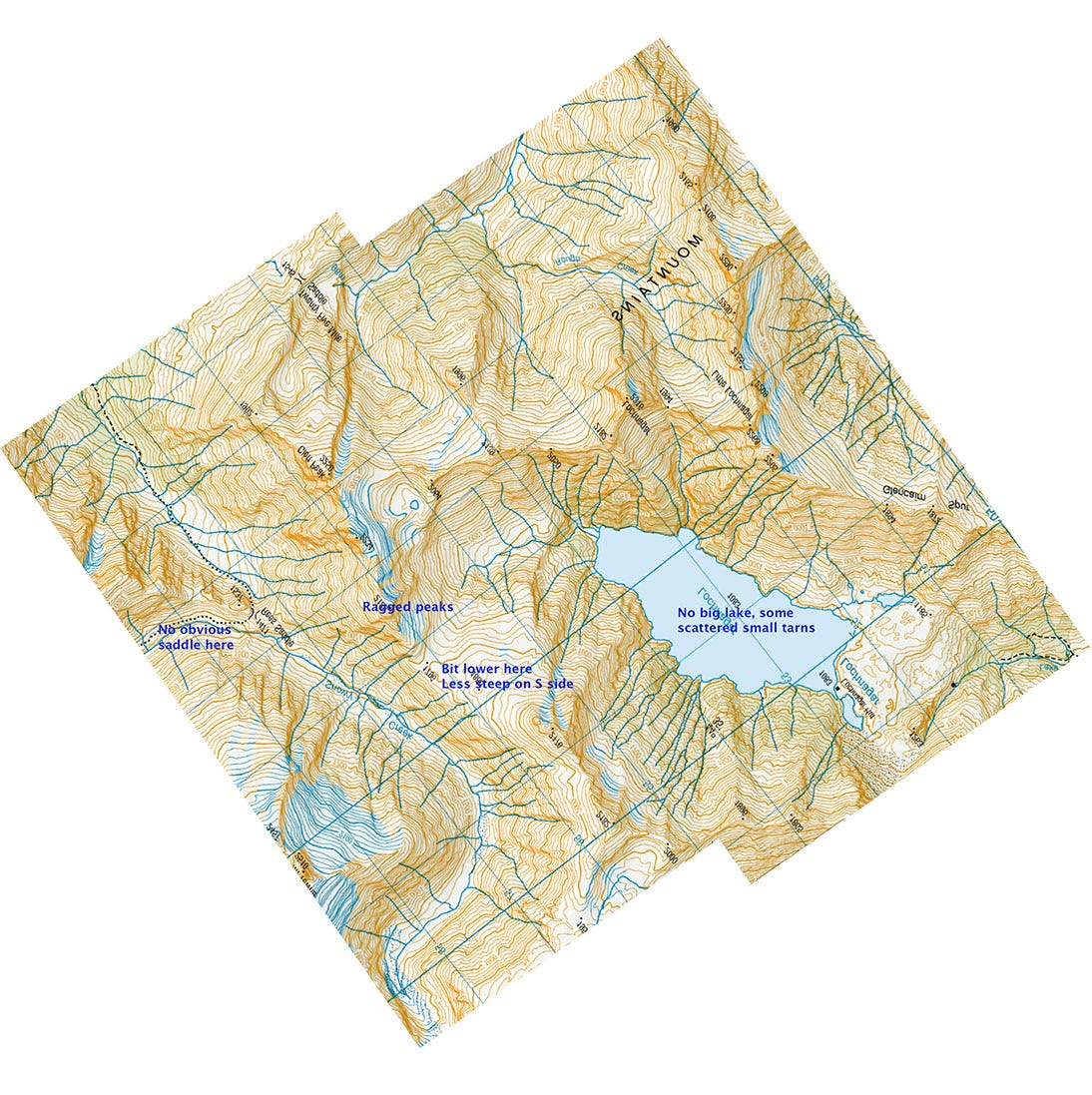

This is the headwaters of Snowy Creek on the Rees-Dart Track in New Zealand's Southern Alps. I did use a heavily modified map of this area to help orientate myself during the writing, but it hadn’t been specifically in my mind while writing the first drafts. (You can see this map at the end of this post.)

This is Monte Paterno in the Dolomites, which again isn't a specific match, but did give me the cover image for The Sundering Wall. And yes, we did climb it, which isn’t quite as daring as it sounds as all the steeper parts are protected by cables (Via Ferrata). Still a great climb, and the summit gives stunning views, including a fairly close look at the North Faces of the legendary Tre Cime di Lavaredo.

I’ve done many other climbs and mountain journeys, one of the first being a solo hike in the Pyrenees in 1991 and perhaps the last of note being the Chemin de Robert Louis Stevenson in the Cévennes in 2012, by which time my focus was shifting ever more firmly towards bikes.

In fact my toughest ever mountain journey doesn't feature in the moodboard photos. More than thirty years ago I did the Biafo—Snow Lake—Hispar La—Hispar trek in the Karakoram in Pakistan. To save money we'd opted only to employ porters as far as Snow Lake. It's a long story and I can't possibly go into all the details here (but ask me if you're interested). Short version, we crossed the Hispar La (altitude over 5000 metres) and walked down the Hispar Glacier carrying rucksacks weighing well over 30 kilos. I didn’t give Jerya, Rodal and Railu quite that much to carry! Apart from one rope, they weren’t burdened with climbing gear, ice axes or crampons, nor (as I was) with two camera bodies and several lenses.1

That trek was also the closest I've come to walking without a map. See below for the map we did have, which I'd photocopied from an Italian expedition book (as you can tell from the image, 'Ghiacciaio' meaning 'glacier'). The Hispar is about 50km long and the uppermost reaches are missing from this image. The 'x's show where we camped so you can see we didn't make big distances most days. (I’ve mentioned this trek before, along with other musings about maps).

I couldn't send my characters on a journey like this because no one in their world knows the first thing about glacier travel and they’d never heard of ice axes and crampons. On the other hand, though this map is pretty darn sketchy and we had to figure out most of the details for ourselves, we still had a lot more information than Jerya, Rodal and Railu do.

Most of all, we knew that people had been this way before and that there were beds and hot meals at the end of it. The three companions have no idea what they will find or whether the crossing is even possible, and that's plenty to contend with. Their loads get lighter as they go on, because they're using up their food. Lighter loads are great, but also deeply worrying when you don’t know when or even if you might be able to replenish your supplies.

We only had to make it to Hispar village—where, after several weeks on reconstituted food, fresh eggs and chapatis gave me one of the most memorable meals of my life. In conjuring mountain journeys for the stories, I’ve tried to remember the importance of food, and other simple things like not having anywhere flat to lie down. It’s all part of the experience.

And having looked at some of my own mountain journeys, next time I’ll consider a few notable examples in fiction by other people. If you have any favourites, I’d love to hear about them.

Confession time; I finished the trip with one fewer lens than I started. On the jeep ride before we even started trekking my zoom lens ingested a bit of grit and would no longer focus at distance. Faced with the prospect of carrying its dead weight for three weeks… well, it ‘accidentally’ disappeared down a crevasse. This seemed like a disaster at the time but I came to realise that the limited choices I had left might actually be helping me, and certainly taught me a lot. (For the photography nerds among you, I did the rest of the trip with 24mm and 50mm lenses and a 2x teleconverter.)