In case you’ve missed it, the Tour de France has just completed its first week. Apparently there’ve been one or two other sporting events taking place this week, but I haven’t been following them; and I’m aware that not everyone follows Le Tour either, notwithstanding its status as the world’s greatest annual sporting event.

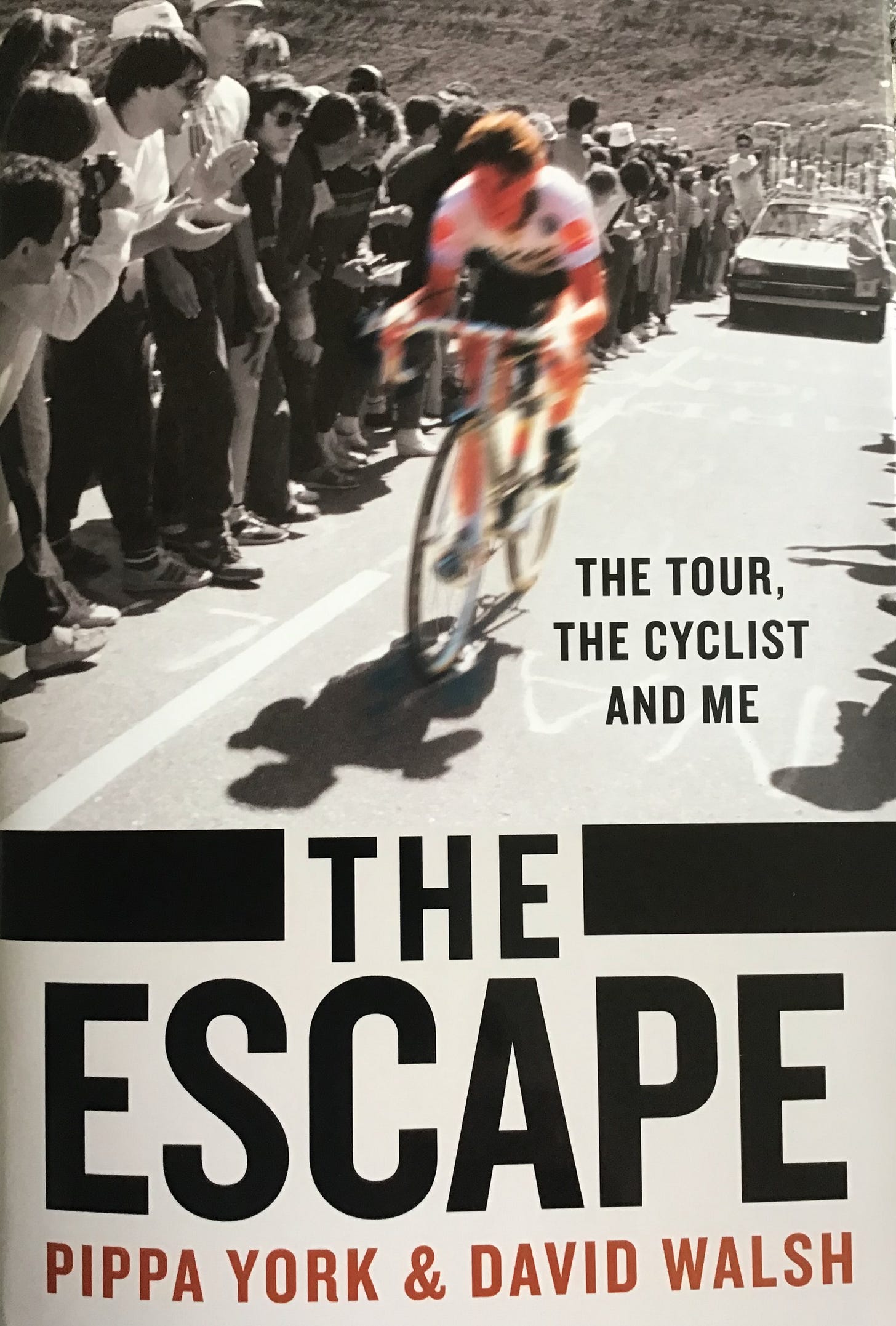

So why would anyone who doesn’t follow cycling be interested in a book about it? Why bother writing a review at all when cycling makes only occasional appearances on my Substack and surely has little or nothing to do with why (for which many thanks) any of you Follow or Subscribe? Because The Escape is a book that is about much more than cycling, or even sport in general.

Most obviously, it deals with important topics like gender transition, and the wider culture around gender (notably in working-class Glasgow in the 1960s and 70s, and European cycle racing in the 80s and 90s. For anyone with an interest in this area, it comes at it in an intriguing and (as far as I’m aware) original way; and if you’re new to some of this, and not put off by the sporting element of the book, it seems to me it could offer a good route in.

Before continuing, a word about the title. To me as a long-term follower of bike racing, it immediately suggests multiple meanings. In this context, Escape from being trapped in the wrong kind of body will occur to everyone. However, it’s also a term with a specific meaning in cycling, though in English the term 'breakaway1' or just 'break' is more commonly used, even in direct translation of the French échappée. This is when one rider, or a small group, elude the clutches of the main peloton and attempt to ride to the finish2 without being recaptured.

A bit of background: Pippa York was born Robert Millar in 1958. From an early age, young Robert3 would dress up in his sister’s clothes, and later venture out him/her self. to buy girl’s shoes and clothes But riding a bike, and later racing, were important too. It’s not fanciful to see these as sublimation or displacement activities, but as a lifelong cyclist myself I’d caution against overdoing such an interpretation. Cycling is an intrinsically appealing activity and for a kid growing up in a working-class neighbourhood, it would undoubtedly offered a sense of freedom and a chance to escape to a different environment.

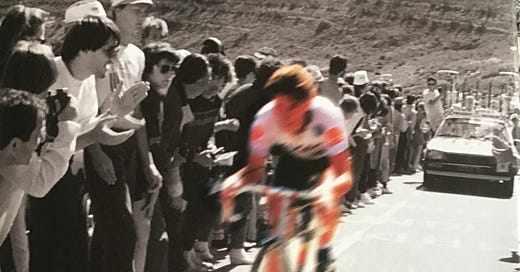

To cut a long story brutally short. Robert Millar raced professionally in Europe from 1980 to 1995, with major achievements including winning the climbers’ classification at both the Tour de France (1984) and Giro d’Italia (1987). It’s also reasonable to suggest that he would have won the 1985 Vuelta a España but for collusion among Spanish teams and riders on the final stage. This would (should) have been the first Grand Tour win by a British male4 rider, 26 years ahead of Chris Froome’s 2011 Vuelta win5.

It seems the gender issues were partially backgrounded during this period but clearly did not, and would not, go away. In the book Pippa recounts several occasions when Robert caught sight of a woman standing at the roadside or watching a podium ceremony and experiencing a profound longing to be her; to be at ease with his/her own body as the other appeared to be.

Around the end of the 90s and into the 2000s Robert Millar all but disappeared from public view, not fully returning into the open until 2017, post transition, when she—under her new name—resumed a career in journalism, including stints as part of the ITV commentary team at the Tour de France. One strand of The Escape is built around transcripts of conversations between her and the well-known cycling writer David Walsh (who played a key role in the exposure of Lance Armstrong’s doping and duplicity). These conversations, mostly captured while driving around France following the Tour, can seem rambling, but shed much light on York’s individual journey to living openly as a woman

.

The other main strand is a more conventional biography, from early days in Glasgow to the racing career, protracted progress towards full transition, not helped by the unscrupulous and exploitative intrusion of the reliably odious Daily Mail.

This unusual structure underlines that this is anything but a conventional biography/autobiography, but I suspect it’s the only way Pippa York could tell her story at this stage in her life.

For me it reinforces the message that every trans experience is an individual one. This shouldn’t be a surprise, but there is a tendency in some quarters to view all trans people, especially trans women, as the same. The story also makes nonsense of suggestions that ‘trans activists’ are busy ‘indoctrinating’ and ‘recruiting’ young people. The young Robert Millar had no trans role models, encountered no activists, didn’t even have any readily available vocabulary to describe what he/she was feeling at a very profound level.

Before I transitioned, people felt I was normal and I felt I was weird.

Now people think I’m weird and I feel that I’m normal.

Pippa York

To be clear, there are significant passages in the book that readers who aren’t followers of cycling, and more specifically cycling in the latter part of last century, will probably want to skip over. I would recommend doing this rather than avoiding the book altogether, because there’s a whole other side to it. For me it provides one of the most illuminating trans memoirs I’ve read. I think there are two main reasons for this.

The cycling connection is one; I was already a fan before Robert Millar’s career began, indeed raced myself (at a much more modest level) in the late 70s and early 80s. I followed the professional scene as best I could, relying on the pages of Cycling ('The Comic' as we always called it) and sporadic reports in The Guardian rather more than the TV coverage, which rarely extended far beyond the Tour de France. In those days any sort of British success 'abroad’ was a rarity and we often fell back on Irish riders like Stephen Roche and Sean Kelly for vicarious glory.

But there’s another, more personal, element. Pippa York is little over a year younger than I am, so the world in which young Robert tried to come to terms with his/her sense of being a girl trapped in a boy’s body feels very familiar, in a way that doesn’t apply to other trans memoirs I’ve read, such as Jan Morris’s Conundrum or Laurie Frankel’s This Is How It Always Is (okay, that’s a novel, but deeply rooted in the author’s experience as mother of a trans daughter). Morris was from my parents’ generation (in fact a few years older); Laurie Frankel is more than a decade younger than I am and her daughter, obviously, that much younger again.

I didn’t face all of those feelings, but I never quite settled comfortably into the expectations that society loaded onto boys. So there’s one particular observation from Pippa that really struck home:

They have no understanding that you failed at being a man. You haven’t been able to be a man. You might have functioned really well in one or two areas when you were a man, but the rest of the time you failed. What you really needed was to change into what you are now.

This resonates with me—because it’s not only trans people who sometimes fail at ‘being a man’. Lots of us 'fail’, to a greater or lesser extent, to live up to socially determined expectations and we still need to be more critical of those expectations instead of making individuals feel like they’re not just at fault but actually faulty. With a resurgence in the cult of masculinity promulgated by the likes of Andrew Tate, Jordan Peterson, and Elon Musk (whose treatment of his own trans daughter is beneath contempt), The Escape could not be more timely.

The Breakaway is the title of the autobiography of Nicole Cooke, one of Britain’s finest cyclists—remember how she started the gold-rush of medals at the Beijing Olympics?

This is a great deal harder than it sounds, for reasons both tactical and physical. As simply as I can put it, air resistance assumes much greater importance in cycling than in slower sports such as running; riding behind another can save 25% or more of the energy expended. A group working together and taking turns to lead while the rest get some shelter behind has a clear advantage over a solo rider—provided (and here’s the rub) they continue to cooperate efficiently.

I fully understand about deadnaming, and how offensive it is for many, but it seems appropriate here to use the original name—not least because Pippa herself does so in her account of her early years as Robert.

Nicole Cooke, already mentioned in one footnote, won the women’s Giro d’Italia in 2004 and Tour de France in 2006 and 2007.

Froome was declared the winner retrospectively after Juan-José Cobo was disqualified for doping.

Since 2011 British cyclists have claimed 11 more Grand Tours: six more for Froome, two for Simon Yates, one each for Bradley Wiggins, Geraint Thomas, and Tao Geoghegan Hart.

Great stuff, this Jon. A handy reminder during Tour season that each rider probably has dozens of things going through their mind that aren't related to the race, too.