The Austen Connection

There’s a slight change of plan here today. I had intended to post about world-building but the writing on that was going more slowly than I’d hoped, and I think it needs a little more time to settle before it comes clear. Like cask ale. So let’s hope for a fine pint next week.

And then Jane Austen, as it were, dropped into my lap.

Yesterday, The Bleating Goat, Jonathan Porteous’s Substack (recommended) announced the results of a reader poll for The Greatest UK Novelist of all Time. And the clear winner, with 44% of votes, was Jane Austen.

I’ve already posted something about my discovery of Jane Austen, so what follows is the very short version.

I began, as so many do, with Pride and Prejudice, after picking up a copy in a bookshop in Islamabad, Pakistan, in 1990. We’d been on a trekking trip in the Karakoram, and I was feeling literature-deprived, so was delighted to come across a bookshop full of English-language books. I basically read the whole book on the flight home, and I’ve loved Austen ever since.

However, which one I’d name as favourite; that’s shifted over time. Predictably it started out being P&P, before Sense and Sensibility staged a neat overtake, though that may owe something to Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet… More recently, I’ve found new things in Northanger Abbey, with its tinge of metafiction, but after a recent reread of Persuasion it’s all up in the air again. Maybe it’s an age thing…

A couple of paragraphs back you might have found yourself wondering what a hairy-arsed climber/trekker sees in the emotional journey of a 20-year-old girl in polite (emotionally repressed) society of 200 years ago. If so, you might want to re-examine your stereotypes. After all, mountaineering has the richest literature of any sport (if you count it as a sport at all); for further evidence see Ronald Turnbull’s excellent 'About Mountains' Substack.

Not that there’s much about mountains in Jane Austen; the promise (unfulfilled) of a trip to the Lake District in P&P is about as close as we get. Even the sojourn in Lyme Regis in Persuasion doesn’t take us into the dramatic landscape close by (for that, try The French Lieutenant’s Woman). In fact, the depiction of landscape of any kind is not Austen’s strongest suit; she’s much more about the interior landscapes of her characters.

Apart from that, what can I say about Austen that hasn’t been said a thousand times before, and better than I could? The subtlety, the sly wit and affectionate mockery, the deftness of the prose, the hidden depths… these are all well-worn themes. And she is, of course, fully and unblinkingly aware just how few were the options for women (of any class) in her time. In her overstrung way, no one expresses this more clearly than P&P’s Mrs Bennet.

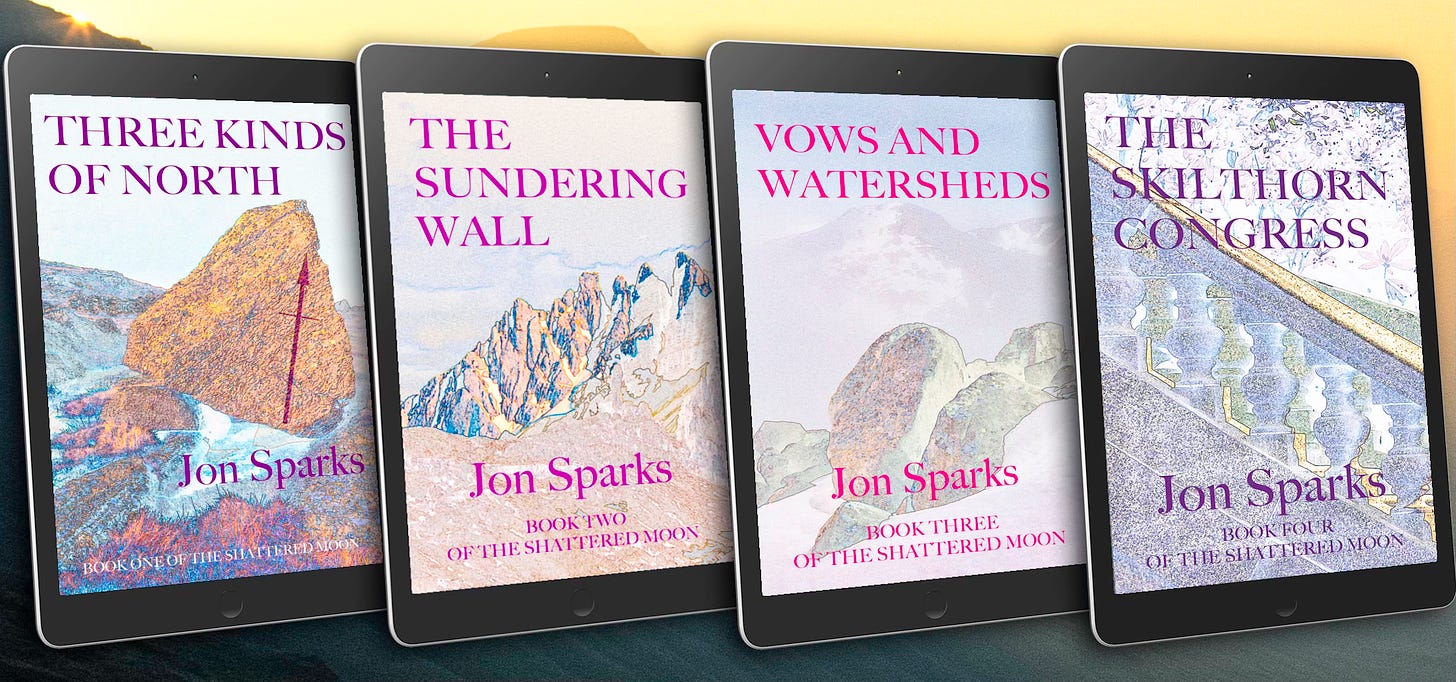

And this, I think, is one of the points of connection; one of the reasons I’ve come to the conclusion that, albeit subconsciously, Austen has been a significant influence on the world of The Shattered Moon. So much so that I have, on occasion, pitched the Shattered Moon series as ‘Jane Austen meets Earthsea’. And not entirely tongue in cheek. (And one my best-loved Le Guin novels, Malafrena, must be in the mix somewhere; is it just coincidence that it’s set around 1825 to 1830—just a decade after Austen’s death in 1817?)

Let’s first consider the ages of the principal characters, noting that at the start of Three Kinds of North, Jerya is 19 and Railu still 18. Ages aren’t always stated in Austen’s text, but many Austenites have examined the question.

Lizzy Bennet: 20 (She tells the tyrannical Lady Catherine de Bourgh "I am not yet one-and-twenty");

Elinor Dashwood: 19 (but somehow comes across as older, in a way Lizzy does not. A 36-year-old actress playing her was still a stretch, though if anyone can carry it off it’s Emma Thompson);

Emma Woodhouse: 20;

Fanny Price: 18 (in the main part of the novel; she’s considerably younger at the start);

Catherine Morland: 17;

Anne Elliot: 27 (again, comes across as older, with frequent references to her having lost her bloom and so on).

Which of these might align most closely with my characters? For Jerya, the obvious nomination is Lizzy Bennet, a spirited young woman and, by the standards of her time, a free thinker. Of course, for all her intelligence and originality, Lizzy seems to harbour no real ambition beyond marriage and, presumably, children, whereas this is exactly the fate Jerya seems to be avoiding. And—spoiler alert—in the yet-to-be-published Book Five, we have another young woman explicitly confronted with a choice between the conventional female role and some other, less certain, future.

For Railu, if it’s any of them, it’s Elinor, though maybe there’s some of Anne in her too, especially the side of her that frequently ends up caring for others.

And a quick mention for my other MC (for the first two books), Rodal. He’s not an aristocrat, of course, though by the standards of his and Jerya’s home village he’s a very good catch. But he’s a plain, practical, outdoors-y kind of guy, which hardly describes any of Austen’s main male protagonists. He’s perhaps closer to Caleb Garth in Middlemarch, though with a strong dash of Fred Vincy too. And if Hedric, who comes to the fore in Vows and Watersheds, is akin to anyone in 19th century literature, it’s Roger Hamley in Wives and Daughters.

But all of this demands a strong caveat. None of my characters are consciously based on any one individual, in life or in fiction, with one partial exception; I did borrow a few traits for Hedric from a fictional character, but not one in Austen or any other 19th century book. Three Kinds of North and The Sundering Wall were done and dusted before I even considered any parallels, so any influence at work has been subconscious. Which doesn’t, of course, mean it’s not there.

There may be a slightly more direct connection in the depiction of one key location, the great house of Skilthorn, which is first seen in Vows and Watersheds, and is the main setting for The Skilthorn Congress. You might well think it bears some resemblance to Pemberley, or perhaps Lyme Park (which 'played’ Pemberley in the 1995 BBC adaptation) or else Chatsworth House (used in the 2005 film, and reckoned by many to have been Austen’s own inspiration for Darcy’s home).

However… it’s commonly said that Lizzy really falls in love with Darcy when she sees the magnificence of his house and grounds. I don’t think this is justified by the text, which shows us instead how Darcy is viewed by his servants, his affection and care for his sister; in fact an altogether warmer side of his nature. Of course one can say that a young woman of the time, emphatically not 'in possession of a good fortune’, could hardly fail to be drawn to the prospect of such wealth. Be that as it may, Jerya’s first sight of Skilthorn engenders a very different reaction; she’s first intimidated, and later repelled.

All the resolve she'd mustered seemed woefully inadequate as she rode up to Skilthorn. It was close on a mile from the lodge to the main house, the drive winding artfully through a park that seemed devoid of people, populated only by fallow deer that gazed with mild curiosity as she passed. When the main house came fully into view, mirrored for even greater effect in a long winding lake, it was all she could do not to turn her horse right around and scuttle back homeward.

Vows and Watersheds, Chapter 39.

In The Skilthorn Congress, when (major spoiler alert) she’s mistress of it all, she says to Railu, "Ghastly, isn't it?"; and she bends her efforts to making better use of it. The results will become clearer in Books Five and Six.

Again, however, if Pemberley/Lyme/Chatsworth were in my mind as Skilthorn first appeared, they were only there at some level below the conscious.

It’s only during the writing of The Skilthorn Congress, and even here only post first draft, that I’ve thought consciously about any Austenian (is that a word?) connection or influence, but I think it’s there, perhaps above all in the reticence of some characters and some of their conversations. If Railu, at the time of the first two books, was closest to Elinor, she’s now (at age 32), got more in common with Anne. And then there’s Mavrys and, now I come to think of it, if she’s like any Austen heroine, she’s Catherine Morland. Even the age, 17, is spot on, but there’s also the role of her active imagination and a tendency to over-dramatise a situation. There’s even a bit of creeping around by night. But Catherine’s ultimate destiny, like every Austen MC, is to marry, which Mavrys is actively seeking to avoid. (And to marry a man, which… but that’s a spoiler too far.)

Conclusions? I think what’s clear is that Austen’s influence on me is almost entirely indirect and inexplicit. I’m not writing fan-fiction, pastiche, or tribute. There are many excellent examples (and a few not so excellent) of this, one of my favourites being The Other Bennet Sister by Janice Hadlow—try guessing which of the five sisters is 'the other' before you follow the link. I hope the influence is there, at least occasionally, in my writing, in the way characters don’t always say exactly what they’re thinking, in the way passions are held in check. And I’d like to think Austen and her characters are one of the ways I’ve been opened to female perspectives and female voices.

And if you’ve read any (or all?) of my novels and you see an Austen connection—perhaps one I haven’t mentioned, maybe even one I’ve never considered; or if you see any other literary influence at work, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

I enjoyed reading your engaging & insightful essay. It is so encouraging to read that your exposure to Jane Austen’s writings has made you more sensitive to women’s resonant voices in life & art. You make a compelling & welcome case regarding Austen’s universality for male readers. Virginia Woolf would be pleased!

I've just bought book 1 of your series. You've intrigued me. I can't promise when I'll read it, as we all know what a writer's TBR looks like ^^' but it sounds fantastic!